Saved from the Clutches of Maya

“My father and the coach at UCLA were pleased with my volleyball successes, and my mother was satisfied with my academic work. But I wondered if Krishna was pleased.”

I was born in Los Angeles in 1949. My parents were avid volleyball players. My father had been one of America’s best, and my mother had been a third-team All-American. I started playing volleyball when I was for. I passed through school easily. Sports dominated my free hors, and generally my childhood was a happy one. With adolescence came dating and more sports, and I left high school with a scholarship to UCLA.

In college my motto was “Success,” and my main ambition was simply to enjoy life. My grandfather had confided once to me that “Money is God.” I wasn’t sure about that, but neither was I sure about God. I evolved to agnosticism.

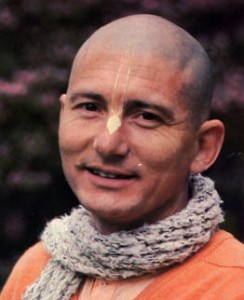

One warm Friday evening, June 9 1970, as I strolled through the campus village, I heard someone call my name. I looked around and didn’t see anyone I knew. Continuing on my way, I heard someone call again. I focused on the only possible source of the sound a saffron-robed, shaven-headed, bespectacled man about my age standing alone between a restaurant and a cinema.

Somewhat startled, I answered, “Yes?” to which he replied, “Don’t you recognise me?”

Straining to get a closer look, I realised who it was.

“Beard! Beard, is that you?” I cried.

“It’s me,” he said reassuringly.

Bob Searight was his real name; Beard was the nickname he’d caught during his volleyball career at UCLA for sporting an extraordinary long black beard. I had just completed my third year, and he had graduated the year before in engineering. His way of life had been awfully similar to mine; in fact, I had last seen him six months before at the beach with two girlfriends.

“What in the world happened to you?” I asked.

“I joined the Hare Krishna movement three months ago,” he said.

“My God, I don’t believe it!” I responded candidly.

Up to that time, me encounters with Hare Krishna were the musical play Hair and the occasional sight of a group of them dancing and chanting on Hollywood Boulevard. My date and I had chuckled as we passed the small clan of cymbal- and drum-playing devotees, who we guessed were burning incense to enhance their drug experiences. I just couldn’t have cared less about them.

Bob serenely explained how he had experienced a higher consciousness that led him naturally toe renounce material pursuits, epitomised by meat-eating, intoxication, illicit sex, and gambling.

I couldn’t believe Beard was saying these things. I challenged his newly discovered denials. Especially dubious was the sex stricture.

He explained how illicit sex was a waste of valuable human energy. As for his vegetarian diet “Everything we eat,” Bob explained, “should be offered first to Lord Krishna, who created everything, and who doesn’t accept animal flesh. Besides, it causes senseless cruelty for the sake of our taste buds. And intoxication further bewilders the already illusioned soul into dreaming and degradation.”

I fired question like bullets, but his answers were convincing, and they destroyed many of my prized conceptions. There was a certain sweetness and peacefulness in Bob’s demeanor. His transformation loomed impressive and attractive.

To support his statements he quoted Bhagavad-gita As It Is and other ancient Vedic scriptures. He explained that Krishna is accepted as God my many great Vedic sages. We are all Krishna’s eternal servants, and if we revive our relationship with Him through bhakti-yoga, or devotional service, our life will be sublime. He told me how Krishna had come five hundred years ago as Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu to teach the chanting of the maha-mantra Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare as the process for self-realisation in this age.

“We are not these bodies but the eternal spiritual soul within. So all our endeavors for worldly pleasures are nonsense.”

“Even volleyball?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied, “just a waste of time.”

After an hour’s discussion, I decided to swear of the four sinful activities Bob had mentioned. Although I was proud, I felt thoroughly defeated. But I was happy. I bought a Bhagavad-gita As It Is, by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Bob also handed me a Back to Godhead magazine and a package of Spiritual Sky incense.

We walked around the block to where a few dozen devotees were singing Hare Krishna and dancing. It was irresistible. They were surprised when I joined them and started chanting with my arms upraised just as they were doing. They invited me to a Sunday Feast at the temple, and I promised to come.

I drove home and dove into the Gita. Line after line, page after page, the wisdom issued forth like and irrepressible geyser bathing my parched heart. I used to sing a song, “What kind of fool am I, who never fell in love, … a lonely cell in which my empty heart must dwell?” Although in my search for a perfect lover I had never thought of God as the one, now I learned that our loving propensity is properly reposed in Him alone. Other earthly relationships, based on individual or mutual gratification, are not really love but lust, at best faint reflections of our original relationship with God. Sensual desire produce frustration, karmic reactions, and more births in this world of suffering, whereas transcendental self-realisation produces eternity, knowledge, and bliss.

After reading for hours, I finally dozed off and awakened shortly after 6:00 A.M. for the Volleyball Beach Championships in San Diego. I ate a breakfast of fruit and nuts and drove two hours to San Diego, chanting Hare Krishna the whole way.

My career in volleyball had been successful: I was voted Most Valuable Player by the NCAA (National College Athletic Association) for 1970, and I was headed for the U.S. Olympic team. My father and the coach at UCLA were pleased with my volleyball successes, and my mother was satisfied with my academic work. But I wondered if Krishna was pleased.

As I stepped out onto the court for the first match, Krishna’s words echoed in my head: “Whatever you do, whatever you eat, whatever you offer or give away, and whatever austerities you perform do that as an offering to Me.” I picked up the ball and froze.

After a long pause, I told a teammate I couldn’t play and confessed my plan to take up Krishna consciousness seriously. He graciously appreciated my resolution. Others didn’t, however, and they expressed their disapproval to me as I headed toward the parking lot. Their pleas proved to be of no avail; my mind was determined.

At the Sunday Feast at the Los Angeles temple, I bowed on seeing the founder and guru of the Hare Krishna movement, Srila Prabhupada. Krishna could not have sent a more suitable person to dispel my hesitance. Even his authentic stature as a 75-year-old Indian swami, fluent in Sanskrit and the Vedic conclusions, helped disarm my resistance.

I told my family and friends that I planned to become a Hare Krishna devotee in six months. But the next week proved awkward, with my novice attempts at abandoning earthly possessions. I gave away some new clothes and stereo equipment to close friends, and, in an unconventional twist, I took my girlfriend to the temple for a date. I had hoped she and my friends and my parents would share my enthusiasm, but they certainly did not. They thought I was crazy.

Day by day my material attachments loosened. By chanting Hare Krishna I lost interest in intoxication, volleyball, and feminine lures. By tasting delicious Krishna-prasadam I lost the taste for other foods. I was convinced that the knowledge I was receiving surpassed all other education. In short, Krishna consciousness became paramount for me.

Although I was very happy about becoming a devotee, I tried to look at Krishna consciousness objectively. My reasoning went something like this: If Krishna is real and His promises for bliss in the afterlife are valid, then accepting His instructions brings gain; conversely, rejecting them brings loss. If Krishna consciousness is not real and the soul does not exist, then afterlives are meaningless and only this life counts. If only this life counts, then gaining pleasure here is the goal. Since the pleasure I’m experiencing now is at least equal to that achieved from worldly pursuits, I have nothing to lose but everything to gain in Krishna consciousness.

I also reflected on the economics law of diminishing marginal returns, which states that the more one tries to enjoy a material things, the less one enjoys each successive unit of that thing. On the other hand, Krishna teaches that spiritual pleasure is an unlimited ocean of expanding joy. Repeated experience had convinced me of the truth of the former statement, while the latter proposition was beginning to sound tenable; undoubtedly, the more I became involved with Krishna consciousness, the more I liked it.

I moved into the temple the next Sunday. Despite the austerities, I felt at home with Krishna and His devotees. My parents felt betrayed, though. “What in God’s name are you doing?” my mother asked.

I was as shocked as they were, since honestly the last occupation I’d ever expected to adopt was to be a Hare Krishna devotee. Only a week before I didn’t know a svami or yogi from a fire-eater or a cartoon bear. It must have been the causeless mercy of Krishna that arranged everything so swiftly.

On my very first morning at the temple, after breakfast I reported for duties to the temple commander, Visnujana dasa. “Please go and find Ekendra,” he said, “and he’ll show you how to wash Krishna’s cars.”

I found Ekendra, a five-year-old boy outside near the cars. A little amused, I spoke up, “I’m supposed to help with the cars.”

“Yes,” he said, “take that bucket with the soapy water and sponge and rub of all the dirt first.”

I happily did as I was instructed, somewhat marveling at the efficiency level here. We talked a bit while cleaning, and he asked me a question about Krishna philosophy. I answered, “Well, I’m not sure, but I think…”

“Don’t speculate!” He interrupted.

That was first day’s lesson.

The next month we all joined Srila Prabhupada in San Francisco for the annual Ratha-yatra parade and festival in Golden Gate Park. Just before the procession was to begin, someone brought Srila Prabhupada the first ten copies of the two-volume hardcover Krishna book, fresh from the printer in Japan. He showed them the crowd, drawing their attention to the one hundred pages of paintings, depicting Krishna’s pastimes on earth five thousand years ago. We had only heard of these stories, and everyone was ecstatic to behold the wonderful books.

Then Srila Prabhupada said, “I’m going to sell them for $10 each. Who would like to buy?”

This was the first time I felt a little remorse about having donated all my money to the temple. I didn’t have a penny. And to make it worse, a friend of mine from high school, Tom, happened to be there, and he immediately bought a Krishna book. He wasn’t even a devotee! But he got the mercy anyway, directly from Srila Prabhupada’s hands. In a few minutes all the copies were sold, with not one left for the author.

One of the most memorable parts of the festival was meeting Jayananda dasa, its organiser. He was a transcendental John Wayne. He was marvelous. Big, strong, and friendly, he built the forty-foot-high chariots, got the permission for the festival, arranged for the decorations, the feast, the advertising, and so on. He slept under the cart at night with a band as assistants, and he could solicit dozens of passers-by into helping with the preparations for Lord Jagannatha’s festival. I asked him a question:

“How do you become happy?”

“I don’t know,” he innocently replied. “I’m too busy to think about it.”

But he was always blissful and active, working tirelessly, and he inspired others to do the same.

After the festival, back in Los Angeles, Bob continued to nurse me during my early days, with his friendliness and quotations from scripture.

One day he announced that this day would be the most important day of his life his initiation by a bone fide spiritual master. He received the name Madhukanta dasa. I, too, was initiated by Srila Prabhupada some months later with the name Danavira dasa, “the servant of the hero of charities.”

Srila Prabhupada wrote to me, “You have a very dear friend in Sriman Madhukanta, for he has actually saved you from the clutches of Maya [illusio]…. Be very firm in your vows….”