A Young Man’s Search For Identity Takes Him From Crisis To Krishna

I grew up in Connecticut in the fifties and sixties. Always “the observer,” dissatisfied with the status quo, I saw my parents’ lifestyle as boring and futile. They had to bear the burdens of clothes for the kids, schooling for the kids, toys for the kids, and lip from the kids, and their only reward was a yearly summer vacation. I understood that there had to be more to life than this, so I began investigating my inner potential without depending on the established social order.

I also became disillusioned with my religious training as a Catholic no one seemed to have solid philosophical convictions. One Sunday, for instance, I was on my way to a softball game, but before I could get out the door my mother stopped me: “Aren’t you going to Mass?”

“Well,” I replied, “the purpose of Mass is to love your neighbor as you love God. So how can I reject my friends now?”

Mother made no philosophical retort, and that was the end of my going to Mass.

My two brothers entered the priesthood, but they lost heart. They didn’t find the purity of thought, word, and deed they were looking for. To me, the philosophy that God put us here for a specific purpose appeared unrealizable; no guide or teacher exemplified that higher purpose.

As for “higher education,” I saw the colleges as training grounds for a kind of life I had already rejected. I couldn’t accept such a process of so-called learning.

My life, therefore, became less a scrutiny of people and ideals and more a search for beauty in nature. Having read books by Rachel Carson, Tom Wolfe, Herman Hesse, and Carlos Castenada (whose drug-induced visions were, to me, boring phantasmagoria), I decided to get firsthand realizations from practical experience. I resented the much-advertised culture of gross materialism, symptomized by industrial pollution and hellish factories that corroded people’s enthusiasm for striving for anything beyond the basic necessities and the crassest kind of sense pleasures. In search of an older, more natural culture, I frequented art museums, and thus I developed the desire to use photography and painting to capture delicate moments of the fleeting seasons and record the artistry etched on nature by time. I wanted to show the beauty of nature to people who, sunk in the rut of work-a-day existence, never explored the world.

I enrolled in the Rhode Island School of Photography and became absorbed in nature. In the mountains and at the sea shore, I saw the extremes that living creatures undergo to survive from lichen gripping boulders high in the cold, wind-swept mountains to the gasping sand-fleas flailing their legs to uncover themselves from the sand dropped on them by the pounding waves of the ocean. I felt fortunate not to be trapped in such horrible conditions of life.

But upon returning to the city, I would see that people had willingly placed themselves in similar extreme situations. With the unspoiled beauty of nature only a few hours’ drive away, people foolishly packed themselves together in the physically and mentally polluted atmosphere of the city. I grew disgusted with the prevailing alienation and unhappiness in society and with how people were being taught to accept this crippled condition as normal.

My desire to accomplish something for society and for myself intensified as I came to realize that in practically no time at all, compared with eternity, my life would end.

But what could I do? All occupations seemed to end ultimately in death. Choosing an occupation meant assuming a certain false identity and becoming entangled in a great endeavor to artificially push myself forward as a certain sort of person. Becoming a photographer or an artist wouldn’t solve the problem of death any more than becoming a doctor, lawyer, or movie actor would. The doctor may refuse to die, but surgery and drugs can’t hold back the white sheet being drawn over the cadaver. The lawyer may dig up some appeal from his vast library, but when his time comes he’ll be helplessly ushered out of the courtroom of life. And the actor may play the role of a powerful man, but in his final act his make-up will streak as sweat pours off his feverish dying body.

* * *

After I’d finished photography school and been employed in a photo shop for a couple of years, I came to the conclusion that my intelligence and creativity were being suffocated. So I arranged that my employer lay me off. I passed a winter alone in a cottage on Cape Cod, recording nature with my paintbrush and camera. How pleasant this simple life was: eating vegetarian foods, breathing fresh air, seeing the sparkling ocean and clear sky, and hearing the sounds of wildlife. But as I painted or clicked away from sunrise to sunset, through sunshine and snow and fog, alone in my cottage, I began to feel a little unsettled without a culture to identify with.

On a visit to Boston I met Larry Burrows, a friend of a friend. We were reading the same book on vegetarianism. One morning, as we shared breakfast, he explained to me that I was not my body but an eternal spirit soul. A little while later he left for Hawaii, to live on a Hare Krishna farm.

I wrote to him and he sent me a copy of Bhagavad-gita As It Is, by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. As I read this book I felt that God had heard all my intimate prayers and was now revealing to me His highest teachings. All my scattered thoughts about life were assembled, clarified, and given a meaningful direction by the mystically familiar teachings of the Bhagavad-gita. It contained the most complete and intellectually satisfying philosophy I had ever read. My mind was doing backward somersaults.

Between letters to Larry, I visited Manhattan, where my brother Tony was studying to be a mortician. While he was at school I walked to Washington Square Park. A flat-bed truck with a colorful canopy pulled up to the perimeter of the park. It was full of Hare Krishna devotees, and one of them (Kapindra dasa) offered me a BACK TO GODHEAD magazine. One article was by a mathematician with a Ph.D.; I was impressed to see that what I’d read in the Bhagavad-gita wasn’t simply sentimental; it was scientific.

In his last letter Larry had suggested I might like the Hare Krishna temple in Boston. So the following weekend I attended the Sunday program there.

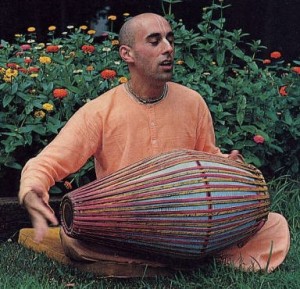

A devotee greeted me at the front door amid inundating clouds of frankincense. Within the temple, shaven-headed men prayed, sang, danced with arms upraised, and played drums and cymbals. Later a devotee spoke on the philosophy of Krishna consciousness, and I asked some questions. During the feast I politely declined most of the cooked dishes, since I was accustomed to raw foods. I spent the night and attended the morning services, chanting Hare Krishna on beads for the first time.

Back in Connecticut, I was surprised to find an unabridged edition of Bhagavad-gita As It Is in the public library. Larry had sent me the abridged version, which I found fascinating, but I found the unabridged edition even more interesting and I read it day and night for a week until I finished it. During that week, my aunt passed away suddenly, and the firsthand experience I gained of people’s emotions during the ritualistic funeral helped me understand Lord Krishna’s teachings in the Gita about “mourning for that which is not worthy of grief.” On this verse Srila Prabhupada comments, “The body is born and is destined to be vanquished today or tomorrow; therefore the body is not as important as the soul. One who knows this is actually learned, and for him there is no cause for lamentation, regardless of the condition of the material body.”

Chapter by chapter, Bhagavad-gita broke down my misconceptions about what I thought I might be and helped me understand that in reality I am an eternal servant of Lord Krishna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Here was the most special of all occupations. Krishna was in fact God, and my real identity in life was to be His eternal loving servant. One evening as I sat alone on my living room floor reading the Bhagavad-gita, I felt inspired. Setting aside the Gita, I lay down on the floor, stared at the ceiling and, feeling protected, prayed, “Krishna, I am Yours. Do with me as You like.”

The following weekend I visited the Boston temple again. I met Aja dasa, the temple president, and asked him if I could join the Hare Krishna society and help spread the philosophy of Krishna consciousness for the benefit of all suffering souls.

He allowed me to stay, and I have never left, for I’ve experienced the higher pleasure a pleasure one automatically feels by serving Krishna, the Supreme Lord. Just as a fish is satisfied only in water, or the hand functions only after feeding the stomach, the spirit soul can enjoy the topmost pleasure only by serving Krishna with devotion. The knowledge contained in Srila Prabhupada’s books Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Caitanya-caritamrta, and others can reawaken one’s transcendental love for Krishna. Therefore, intelligent people should seriously hear and propagate the philosophy of Krishna consciousness contained in these books, for that knowledge will destroy the pangs of material existence and bring them eternal happiness.