Captured by Krishna

A Peace Corps veteran tells how on his first professional photo assignment he became interested in Krishna consciousness.

I was staying with some friends on Long Island, in July, 1970, when Asia Magazine called and gave me my first professional assignment a photo-essay on the Hare Krishna people. I knew that they chanted on the streets of Manhattan, so I rode in on the Long Island Railroad to find them. But when the train pulled in at Penn Station, I had no idea where to look. I surfaced at Thirty-fourth Street and there they were. Just down the street they were dancing and singing, their robes flapping like orange flags against the bright blue sky. I walked up to one young man and asked him if I might take some pictures. “Sure,” he said. Later on, I rode with the group to their temple, on Second Avenue, in the East Village. That summer I did two articles on the devotees of Krishna. In the fall I chose them as the subject of my M.A. thesis. With the consent of my professors, I booked a flight to India, where I planned to photograph the spiritual master of the Hare Krishna movement as he toured with a group of his American disciples. I heard later that one of my professors had remarked, “John will probably go to India and become a yogi and never come back.”

Nothing could have been farther from my mind. I was determined to get my M.A. in photography. During my three years with the Peace Corps in Malaysia, just as a hobby I had taken photos of the Malaysian people. The result had been a successful photo show for the American ambassador. Encouraged, I had decided to study photography at Rochester Institute of Technology.

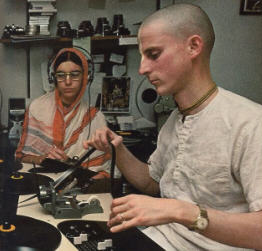

At R.I.T. I had met my wife, Jean, who was a promising young photographer. At nineteen, she had just published her first book, Macrophotography. When I was leaving for India in December, Jean was having an exhibition of her photographs in New York City. We decided that she would stay in New York and join me in a few months.

As the plane took off, I knew that something very exciting lay ahead. Imagine I was going off alone to India to meet some American Hare Krishna devotees, and I barely knew their whereabouts.

I settled back in my reclining chair and opened Bhagavad-gita As It Is, the basic scripture of Krishna consciousness. A devotee named Guru dasa had told me that if I wanted to write a good thesis on the Hare Krishna movement, I should study this book carefully. I began with the Ninth Chapter, “The Most Confidential Knowledge,” in which Lord Krishna says, “This knowledge is the king of education, the most secret of all secrets.” I felt I knew nothing about spiritual life. Although I couldn’t understand theGita very well, at the same time I thought, “Here’s something very profound.”

After landing in Bombay, I looked up an Indian gentleman at an address the New York devotees had given me. He told me the Hare Krishna people were in Surat, a town two hundred miles north of Bombay. Immediately I booked a third-class ticket and caught a train for Surat. It was evening when the train pulled in. Someone showed me the ricksha stand, where rows of lean men stood smoking cigarettes beside their three-wheeled vehicles. “Hare Krishna? Hare Krishna?” I said hopefully. “Yes! I know! I know!” one man shouted and grinned.

I got into his ricksha, and we raced off through the noisy streets into the dusk. The whole town was out strolling. Ricksha bells rang constantly as my driver threaded his way through the crowd of people, bicycles, and white cows. He stopped before a modern stucco house. As I jumped from the ricksha, I noted that standing on the steps was a fair-skinned sadhu in saffron robes.

Inside I found an old friend from the New York temple whose beaming face told me what I wanted to know “Welcome to India!” That night I entered another world. First, my host Mr. Jariwallah gave me a garland of flowers and a silver tray filled with Indian cooked foods and fruits. When I had finished, my devotee friend took me in to meet his spiritual master, His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Srila Prabhupada sat on a pillow, and he looked very stately. A devotee handed him a copy of Asia Magazine and told him I had done an article on the devotees. After looking through the article, he smiled and said, “Yes, that is very nice.” I explained to Srila Prabhupada that I wanted to take more photographs, and he agreed. So, thanks to my picture-taking, I got to spend several hours in his room. He kindly introduced me to all his visitors: “This is John Griesser. He is an expert photographer.”

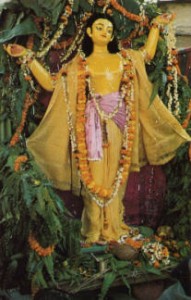

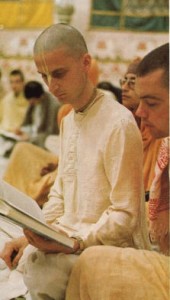

At 4:20 A.M. the next day, about twenty of us gathered in Srila Prabhupada’s room for the morning service. A devotee named Dinanatha dasa sat on the floor and chanted, the drum in his hands exploding with rhythm. Another devotee performed the ceremony. He offered incense, ghee lamps, flowers, and a peacock fan to the Deities Lord Krishna and His consort Srimati Radharani, who stood together on a small marble altar. Everyone sang Hare Krishna to a melodious tune I hadn’t heard before.

Then Srila Prabhupada gave a lecture. I admired his scientific descriptions of how the body is formed and the soul enters into it. His talks revealed a keen philosophical intelligence. My mind was satisfied when I heard his version of the mystery of birth, death, disease, and old age. He also explained that whatever insures people’s spiritual happiness is the highest welfare work. I understood that the desire to alleviate suffering is the basic motive of a genuine guru.

I’ve often thought how lucky I was on my visit to India. Some Westerners wander around India for years meeting various yogis and so-called gurus, shopping in bazaars, contracting diseases, and generally getting lost. I didn’t even go to India with a spiritual aim. I simply wanted to finish an M.A. thesis and increase my photographic skill. Yet what a stroke of luck on my first night in India, I met a pure devotee of Lord Krishna.

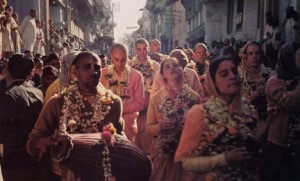

In Surat every day was a huge festival. I had a rare vision of an older, more spiritual India than I’d seen in Bombay. Around nine o’clock every morning, the devotees went out chanting in the streets, and I followed them with my camera. The welcome they received is one of my best memories of India. At each house someone would come out to garland the devotees, and after a few minutes the devotees’ ecstatic faces would be hardly visible behind the flowers. Bolts of colorful cloth hung across the narrow streets, from balcony to balcony. Ladies showered flowers down on us from their windows. Indians naturally respect devotees of the Lord, and when the devotees happen to be young Westerners, they are even more popular.

I was glad to see the devotees in their glory, because I respected them as people and as friends. There was Guru dasa, a large and jolly person who himself took photographs of everything. There was Yamuna, his wife, a gifted singer who had introduced radio audiences to the Hare Krishna mantra when she recorded it with George Harrison on Apple Records. There was Tamala Krishna, the group’s leader, whose determination I admired. And there was Giriraja dasa, who offered me his cheerful friendship. These special people helped me to appreciate Krishna consciousness.

After the festival in Surat, the whole party moved on to Allahabad, about three or four hundred miles west of Benares. I went to Bombay to develop my film. After a few days I took a train to Allahabad and joined the devotees.

At Allahabad it was the time of the Kumbha Mela, a festival that happens every six, years. The Kumbha Mela draws some six million people to the meeting point of three sacred rivers. Pilgrims come by foot, by camel, and by train. Prominent yogis even come on the backs of elephants. Somehow six million people crowd together at the meeting of the Ganges, the Yamuna, and the Sarasvati rivers to take their bath at that astrologically correct time.

The night I arrived, the Allahabad train station was packed. I hailed a ricksha driver and said, “Take me to the Ganges.” After he’d peddled through the blackness for about half an hour, I wondered whether he was taking me to a secluded place to rob me. I asked, “Where is it? Where is the Ganges?” He motioned with his hand, “Wait just wait!” in the bossy way that ricksha drivers have. Suddenly he stopped. The night was so dark that I couldn’t see anything, but he was signaling, “We’re here.” I got out, paid him, and started walking along what turned out to be a high cliff. As far as I could see below me, there were twinkling lights. I now realized that the dark strip running between the two fields of light was the Ganges and that the lights were millions of torches, candles, ghee lamps, and small hurricane lamps dotting the campsite of the Kumbha Mela. The smell of cow-dung fires floated up to my nostrils, and I heard a great hum coming from below. It was the mingling of many mantras and prayers. I was awestruck.

Carefully yet quickly, I climbed down the side of the cliff to the maze of tents below. At the bottom I spotted a policeman and asked him to help me find the American devotees. He led me to the nearest cluster of tents, which stood facing the dirt road. Once again I’d caught up with the Hare Krishna people.

The next morning, the devotees formed their usual chanting party along the road beside the Ganges. The sight of these twenty young men and women dancing along the road with drums and cymbals was a joy to the other pilgrims. They were very friendly toward us. Apparently, they had never seen foreigners who sang and danced like that.

From morning till night, thousands of people streamed into our large tent. They saw our large Radha-Krishna Deities and then took prasada (spiritual food). All the while, they listened to the chanting of Hare Krishna.

I was thoroughly enjoying myself. I could feel that the holy Ganges was purifying me. After bathing in her waters, I felt lighter in body and spirit. An Indian health official there told me, “Science cannot explain why, but the Ganges never becomes stagnant or polluted.”

My life at the Kumbha Mela festival settled into a pleasant pattern. At night I slept on a rug in a tent. In the morning I joined the chanting party, and afterward I helped with the cooking. I was learning how to roll chapatis [flat whole-wheat bread]. There were also opportunities to photograph the yogis. Sometimes they paraded on elephants their naked bodies smeared with ashes, their foreheads lined with red and yellow clay. Others wore long hair and beards and filmy white robes. I got some good pictures of the yogis, but they seemed indifferent to me as a person. One actually laughed at me, as if being a Westerner somehow disqualified me from being there. I could sense that many of the yogis had unusual mystic powers, but I felt that they didn’t have much compassion for other people.

On the other hand, Srila Prabhupada was averse to riding proudly on elephants, but he took an interest in someone like me. At all hours, he kindly discussed spiritual matters with the people who visited him in his red tent. With a small light hanging from above, Srila Prabhupada sat on a raised seat, and his visitors sat on carpets.

He roared like a lion at those who challenged the existence of God, but he was soft as a rose with those who were open-minded. Most often he was simply friendly and charming to everyone. Sometimes when he saw me he would ask, “is everything all right?” About that time, I shaved off my mustache. When Srila Prabhupada noticed, he said, “Oh, that’s very good. You look very nice.”

In Allahabad I also met an American student. He was from the University of Benares, and he invited me to visit him there. A few weeks later I went to see him. I think I wanted to talk to someone removed from Krishna consciousness, to give myself another angle on what I was experiencing. Or perhaps I was just restless. Anyway, in late February I went to the holy city of Benares, or Varanasi.

At my friend’s place were students from Australia, New Zealand, America, and India. One evening I cooked a vegetarian dinner and offered it with prayers before a picture of Lord Krishna. Everyone enjoyed the time-honored Indian dishes I’d learned to prepare in Allahabad. I mentioned that the devotees would soon be in town for a festival, but the students weren’t very interested. At the same time, their talk about their new courses and old acquaintances seemed rather trivial. Krishna consciousness was making more sense than anything else I had come across.

The festival at Benares was to commemorate the appearance day of Lord Caitanya, the sixteenth-century avatar who founded the Hare Krishna movement. The devotees were eager to go to Benares, because there within a few hours Lord Caitanya convinced several thousand scholars to become His disciples. When Srila Prabhupada arrived in Benares, the townspeople honored him as the foremost teacher of Lord Caitanya’s philosophy, and they took him through the town in an ornate coach drawn by four white horses. He seemed to be going from victory to victory on his Indian tour.

That afternoon I went to see Srila Prabhupada at the house where he was staying. He sat under a tree in a sun-splashed courtyard, eating some guda [solidified molasses]. His expressive features lit up with a smile of welcome when he saw me. He was talking in his accented, rhythmic English about his boyhood days in Calcutta, and he described a gracious city, before the crowding and squalor of today. As a schoolboy he had seen splendid Victorian buildings of white marble, surrounded by stately lawns and trees.

Serene and lighthearted, Srila Prabhupada looked at me and remarked, “John, I think that Krishna has captured you.” I agreed. I had known it for quite a while, but now Srila Prabhupada had confirmed it.

After the festival in Benares, we all took a train back to Bombay, on the western coast. By this time I was wondering what had happened to Jean. Krishna had captured me, and I hoped He would capture her also. I expected her to come to India soon, but she’d been delayed. In April I got a letter from her.

She wrote, “I expect to be leaving New York in two weeks, if there are no more complications. Personally, I’m feeling very restless. I’ve learned to be technically competent, but I find myself searching for something worth saying in my photographs. I want to do something positive with my camera something that will make people happier, or better in some way. I have a medium, but no message.”

While reading Jean’s letter, I remembered what Srila Prabhupada had once said: “If one is not in Krishna consciousness, he must be disturbed, because there cannot be a final goal for the mind.” When she finally arrived, I tried to be patient with her and to help her have the same pleasing exposure to Krishna consciousness that I’d had. She went in to visit Srila Prabhupada with the book she had written. He praised her technical know-how and gave her a big garland to wear. She was speechless.

At this time, in the heart of Bombay, Srila Prabhupada and his disciples were presenting one of the biggest spiritual festivals the city had seen in many years. Radha and Krishna Deities stood on a stage inside a huge tent. In this canvas pavilion Srila Prabhupada would lecture to twenty or thirty thousand people every night. White-shirted Indian businessmen and their well-groomed wives took part in the chanting. Everywhere the people welcomed Srila Prabhupada and his disciples. Also, many people invited them to their homes to chant in front of the family Deities and to take some prasada (which might include spicy vegetables, sweet rice, fruit, and sweets, all in little stainless-steel cups).

When the festival ended, Jean and I decided to leave Bombay. Exotic India still attracted our photographic propensities, so we asked Srila Prabhupada’s advice about going off to photograph a country village. He suggested that we go to Vrindavan the small village (ninety miles north of Delhi) where Lord Krishna grew up. It seemed a good way to quench our thirst for the picturesque. I had come to India to photograph the faces of devotion, and Vrindavan, Srila Prabhupada told us, is full of devotees of Krishna.

We took a train to the town of Mathura, Krishna’s actual birth site. From there we rode a horse-drawn cart to Vrindavan. As we entered Vrindavan, sunset was approaching. So we searched for the home of our host, a seventy-five-year-old Indian medical doctor who was a devotee of Lord Krishna. As we drove on, the temples facing the road offered us glimpses of Krishna Deities, and melodious chants rose and fell away. The air smelled of incense and the smoke from cow-dung fires. The streets of the bazaar were jammed with people who had come to see the home of Lord Krishna. When we reached our destination, darkness had set in.

The next day we went out to explore. It was the rainy season, and the greenery was thriving. There seemed to be peacocks in every tree, and small, colorful birds hopped toward us with inquisitive glances. We took photographs of the cows wandering across the gentle green hills or standing on the orange earth. Holy men with wooly hair and simple clothes grinned amiably at us as we snapped their pictures. Then Jean went to photograph the Bengali widows in the temple, and for an hour she joined them in their chanting. There are hundreds of well-known tourist spots all over the world, we thought but the most beautiful of all, unknown in the West, is the land of Vrindavan.

Srila Prabhupada had guided us to a place where his devotees were staying, and we were glad to be with them. Their friendship helped us appreciate Krishna. Giriraja was always telling us stories about Krishna and His brother Balarama as we traced Their steps through the white, sandy roads of the Raman Reti district. Our next-door neighbor was Doctor Kapoor, a retired physics professor whose admiration for Srila Prabhupada was boundless. He often told us how Lord Krishna dwelled within everyone’s heart, and he encouraged us to chant Hare Krishna.

Everything in Vrindavan demanded to have its picture taken from the tiny donkey with his burden to the ancient shops, dwellings, and temples that lined the main streets of the bazaar. Old Bengali widows in white saris greeted us with a friendly “Hare Krishna.” Monkeys leered and threatened from the rooftops of the market. At dusk the bells of a thousand little temples began to ring, mingling with the cowbells of returning herds. In the evening everyone visited the temples to see the Deities.

I thought Krishna must have brought us to Vrindavan on purpose. The land of His pastimes was helping Jean to experience the beauty of Krishna consciousness. I hoped she would be receptive to Srila Prabhupada. Being with him had cleared up my doubts and I was sure that his was the best message Jean and I could convey through our photography.

After a month in Vrindavan, we got a call from Guru dasa, in Calcutta. At his invitation we went to Calcutta and helped publish a special book for Srila Prabhupada’s birthday. The book contained beautiful photographs of Srila Prabhupada and tributes from his disciples.

About two months later, Srila Prabhupada came to Calcutta. After being with him for many months and studying his teachings, I was sure that Srila Prabhupada was a pure devotee of Krishna and that I should accept him as my spiritual master. When I read Krishna’s words in Bhagavad-gita about the qualities of a pure soul, I found that Srila Prabhupada fit the description. He was always glorifying Krishna, he was humble, and he was always trying to enlighten people with Krishna consciousness.

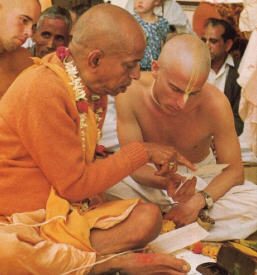

On October 10, 1971, Srila Prabhupada formally accepted me as his disciple. We prepared a fire sacrifice and purchased garlands for him and all the devotees who were to receive initiation. During the ceremony Srila Prabhupada chanted gravely on our prayer beads and then gave them to each of us. He handed me my beads, sanctified by his touch, and said, “Your name is Yadubara dasa.” Thus my spiritual life officially began.Since Jean was not quite ready, she did not take initiation at this time. One day Srila Prabhupada asked her about her family. “They’re all atheists, Srila Prabhupada,” she said.”Do you have a brother?” he asked.

“Yes, he’s an atheist too, and a communist.”

“How did you get here?” he asked with a twinkle in his eye.

“By your mercy,” she said.

“No,” said Srila Prabhupada, “It was by Krishna’s mercy that you came here.”

Later in October, we all went to another festival this time in Delhi. Jean and I got the chance to do publicity and to photograph the important men who visited Srila Prabhupada. Every night we sat onstage and heard him confirm that the most important duty of the human being is to reestablish his connection with God. Many important men came to listen, including the Canadian High Commissioner and the Indian Minister or Education.

I prepared a photographic exhibit by enlarging my eleven-by-fourteen prints at a photography shop in Delhi. After mounting them, I placed them on exhibit stands borrowed from a government office. There were pictures of our joyful dancing and chanting in Surat, Allahabad, Benares, and Bombay.

Another popular feature of the festival was our “Question-and-Answer Booth.” A devotee would sit and answer questions from the visitors. Each day the booth had to stay open until midnight or later, to satisfy all the curious people.

After the festival had ended, Srila Prabhupada took us all on a journey to Vrindavan. We traveled together in buses to visit the places where Krishna danced and swam and performed heroic feats. We went to the Yamuna River, specifically to the place where Krishna showed His mother all the universes within His mouth. Srila Prabhupada felt the water and said, “It is too cold for an old man like me. But you all take a bath. I’ll put a few drops on my head.” The ladies went farther along the river, and the men went splashing into the water. We were very delighted when, a short while later, Srila Prabhupada decided to join us.

One day a question prompted Jean and me to visit Srila Prabhupada in his quarters. He looked magnificent, striding briskly back and forth and chanting, “Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.”

“Srila Prabhupada, shouldn’t we have a spiritual marriage?”

“Yes, that is my desire,” he answered at once, looking pleased with us for having thought of this idea. “Yes, that is my desire,” he said again “that you live happily together in Krishna consciousness.” His confident voice made the whole plan very pleasing.

Afterward, Jean said to me, “Srila Prabhupada’s purity is so attractive that he can convince even a hard-core atheist like me to believe in God.”

Her initiation and our spiritual marriage came on November 29, 1971. Guru dasa performed the ceremony, and Jean received her new name Visakha-devi dasi. Srila Prabhupada remarked that it had been “a very transcendental ceremony.”

Since that time we’ve tried to follow our spiritual master’s advice on marriage. “Marriage in Krishna consciousness is the perfection of married life, because the basic principle is that the wife will help the husband so that he may pursue Krishna consciousness, and the husband will also help the wife to advance in Krishna consciousness. In this way, both husband and wife are happy, and their lives are sublime.”

For the next year or so, we lived in the temple in Bombay, where I acted as secretary. We made a few small films and sent them back to the devotees in America.

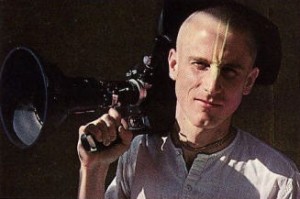

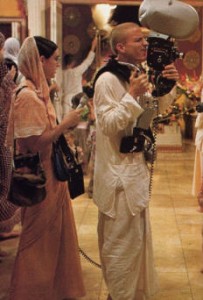

In 1973 Visakha and I flew to New York to start work on “The Hare Krishna People.” We heard we would need six or seven people to make the film, but we ended up doing everything ourselves. I bought a manual of movie-making, and Visakha and I planned out our work. With her doing the sound and me doing the photography, the documentary took ten months. We spent five months shooting in Europe, Mexico, and the United States. Then we settled in New York for five more months to edit. Srila Prabhupada likes “The Hare Krishna People” very much. He’s seen it at least a dozen times and has urged me, “Make more films about Krishna consciousness.”

I’m grateful that my first photo-essay back in 1970 took me to my spiritual master, and that Srila Prabhupada turned that small assignment into a full-time and fulfilling engagement in the service of Lord Krishna. There’s an old Bengali proverb that seems to explain my good fortune very nicely: “By the grace of Krishna, you get your spiritual master. And by the grace of your spiritual master, you get Krishna.”