Shelter Beyond Duality

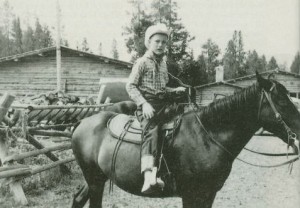

“Life was tough from the start … a slap on the backside. But at age four came my first hard taste of reality.”

THIS IS THE STORY of my life. Or better yet, the story of two lives: the one my spiritual master saved me from, and the one he gave me. Both concern the same person, but one life was temporary, ignorant, and full of suffering, and the other is eternal and full of knowledge and bliss. This is the story of the miracle, for me at least, of how I was delivered from the ocean of material life.

You could say my story begins within the womb. But I know it goes back many lifetimes, to a past too distant for me to know or understand. If cameras had existed that long ago, I imagine we’d see on these pages photos of kings and paupers, animals and men, the famous and the infamous all dying and then being born again. But this chapter of my story begins, like all life stories, from the day I was delivered anew, with a mother and father, sisters and brothers, cousins and nephews.

Life was tough from the start … a slap on the backside. But at age four came my first hard taste of reality: I contracted spinal meningitis. The doctors were experimenting with new drugs, but none of them had proved reliable. I remember seeing my mother cry when they told her what I had. All I knew was a raging fever and lonely months in the hospital ward as doctors desperately tried to save my life. I remember once hearing nurses whispering about my inevitable death. Anxious for shelter, I wondered, “Where is my mother now?”

But after some months the medicines proved effective. I left the hospital a little wiser. I was only four, but I knew more what to expect. Life wasn’t going to be all what the storybooks said.

When I was six, Old Yellar died. He was the neighborhood hound, the best friend of all the boys on the block, our constant companion until the day he crossed the road a little late. The car that hit him didn’t even stop. Some of the boys ran after it throwing rocks. The rest of us cried at Old Yellar’s side as we watched his life ebb away. We pleaded to Mr. Franklin, who came by in his ice cream truck, to save Old Yellar. He just stood motionless, because it was too late. Again a distant thought came into my mind: “Who can we turn to for help?”

As I grew, I mostly learned how to survive. School seemed irrelevant. I be-came disillusioned quickly, my mind pondering the dualities of birth and death, happiness and distress. Nothing would last. That I had seen not the shelter of the womb, Old Yellar, or for that matter even me.

I began to see that others were also perplexed and suffering. Not only people, but animals as well.

But not everyone was sympathetic to how I looked at things. At twelve years old in school we were asked to draw what we’d like to see on the table at the upcoming Thanksgiving Feast. I drew vegetables, no turkey or meat. My classmates saw it as hilarious; my teachers thought it odd. And the day I refused to eat meat my father figured I was downright impolite, and he sent me to bed without supper. As I lay in bed, I thought how hard life is, even if you try to do things right.

At sixteen I made the break. “Maybe it isn’t like this everywhere,” I thought. Perhaps somewhere else I could find a really satisfying life. Sometimes I’d felt I’d come close, especially when my friends and I surfed the waves at Stinson Beach, near San Francisco. Out there, we were free and moving.

With great hope and expectations we packed our gear that summer and headed south. Perhaps in Mexico we’d find the perfect wave. But even as we left, my friends chided me when I said, “But it won’t last forever.”

At San Blas we were thrilled when we caught waves that gave rides a mile long. But the real challenge was around the point, at Rodger’s Bay. There the waves broke in perfect formation. The curl was flawless you could shoot the tube! It seemed perfect. But there was one problem the waves broke onto a coral reef.

I don’t really know what impelled me to paddle toward the reef that day. Some boys challenged me; others pleaded with me not to go. Perhaps I was desperate.

I caught the wave with ease. It was big, beautiful, and long. I quickly turned left, crouched, and suddenly found myself racing into the tube. I was thrilled, exhilarated this was it! But in my excitement I lost my concentration and slipped … right into the deadly reef.

I remember screaming for help as the coral tore into my skin. But in the back of my mind I thought again, “Who can help me now?”

I rolled and tumbled across the rocks and landed close to the beach. Some villagers came and pulled me out. I was fortunate; except for a large gash on my left leg, I had mostly minor cuts and bruises. But my surfboard was finished, and so was my search for the perfect wave.

Back in the States, I reflected that if I couldn’t save myself, maybe I could save others. So I enlisted in the Marine Corps, America’s top fighting unit. My country was fighting in Vietnam to stop the spread of communism. I thought if we could win in Vietnam, perhaps we could bring peace and happiness to the world.

It’s been said that we can see heaven and hell even in this life. That year I saw hell as I went through the ordeal of becoming a killer. But often as we’d fix our bayonets for a practice duel my mind would object, “You don’t really believe in the war, do you? Be honest with yourself you’re only here for name and fame. And you might well lose your life for it.”

One day I approached my authorities and refused to fight. The next several days in jail gave me time to think. “It’s easy to kill but so hard to know what to live for.”

By the time I received my discharge papers, I didn’t know whether to go left or right. I wandered in desperation, thinking how each time I made a step in life I met with frustration and despair. One day in the privacy of my room, I called out to God. “My Lord, I’m in a world of distress! If You’re really there, please give me shelter.”

By the time I received my discharge papers, I didn’t know whether to go left or right. I wandered in desperation, thinking how each time I made a step in life I met with frustration and despair. One day in the privacy of my room, I called out to God. “My Lord, I’m in a world of distress! If You’re really there, please give me shelter.”The next afternoon I wandered into a museum, intent on forgetting myself by browsing through antiquities. An exhibit on India’s culture and traditions caught my eye. As I surveyed the paintings and artifacts, my eyes fell upon the most beautiful painting, marked “Krishna and His Milkmaids.” The scene captivated my attention, and I moved closer to read the text that went with it:

“This scene depicts heaven, where God enjoys eternal life.”

“Yes,” I thought, “that’s what I’m looking for eternal life, a place beyond the dualities of the world. But could it be like this? Who is Krishna, and what is a ‘milkmaid’ anyway?”

I looked around for someone to explain the painting in more depth. But a guard announced that the museum was about to close. Disappointed, I walked out the main entrance and came upon a most amazing sight. Seated on the lawn before me were orange-robed monks with large staffs in their hands. They were speaking intently to a crowd around them.

I inched forward to hear better and was stunned when the tallest monk told the crowd about Krishna and the spiritual world. I learned later that what he was speaking is found in the ancient Vedic scripture Brahma-samhita:

Krishna is the Supreme Personality of Godhead. He lives forever in the spiritual world, beyond the dualities of material life. His transcendental land of Vrindavan is populated by goddesses of fortune, who appear as milkmaids and who love Krishna beyond anything else. The trees there fulfill all desires, and the waters of immortality flow through land made of wish-fulfilling stone. There all speech is song, all walking is dancing, and the flute is the Lord’s constant companion. Cows flood the land with abundant milk, and everything is luminous like the sun. Since every moment in Vrindavan is spent in loving Krishna, there is no past or future.

“That’s it!” I yelled out.

Surprised, the monk turned toward me. “That’s what?” he asked.

“That’s what I’m looking for!” I replied. “I prayed last night. Then I saw the painting in the museum … and now I’ve found you!”

He’s probably on LSD,” remarked a woman to my left.

I composed myself, a bit embarrassed that the entire crowd was staring at me.

But I was determined. Never before had I heard such knowledge, and so concisely explained. I introduced myself to the monk.

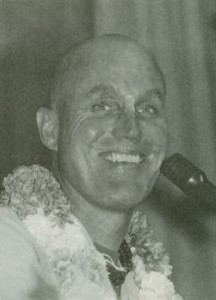

“I’m Visnujana Swami,” he said, “and we’ve come to take you home.”

And so it began this new life, my life as a devotee of Krishna way back in 1971. If I could show you all that’s happened since then, you’d see many photos on this page of singing the holy names and dancing, of feasts and illuminating discourses too numerous to mention or explain. Let it suffice to say that on that day I started home again, beyond the dualities of birth and death, to the shelter of the eternal realm.

Indradyumna Swami travels around the world spreading Krishna consciousness. He’s based at the ISKCON temple in Durban, South Africa.