My Eureka Experience

A few lines from a little book turn a routine evening after work into an Archimedean bath.

A eureka experience occurs when something routine and familiar suddenly triggers a powerful, emotionally charged realization, and you perceive as never before the depth, meaning, and significance of that particular action or statement.

You feel like the Greek mathematician Archimedes felt when, upon entering his bath one day, he suddenly discovered how to measure the density of an object by seeing the amount of water his body displaced. And like Archimedes, when you have such a stirring revelation, you may also feel like dashing through the streets shouting “Eureka! Eureka!”

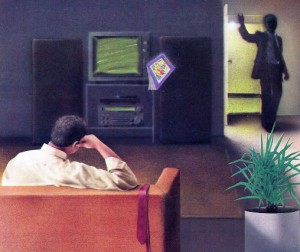

I had my eureka experience one day in May 1973. I’d gotten home from work around five thirty, and as usual I performed my daily rite of watching television with the sound off, the stereo blaring at near peak volume. That was how I’d purge myself of a day at the office of White, Weld and Co., a brokerage house near Wall Street.

My roommate walked in, a big smile on his face, and tossed a booklet in my direction. In deference to the loud music, he pointed to the booklet while silently mouthing “Got that for you.”

I turned down the music and retrieved the booklet from the floor. The title was Krishna, the Reservoir of Pleasure. “Thanks, Kevin,” I said. “I just read a book about Krishna a few weeks ago. Three volumes. Interesting stuff.”

“I saw you reading it; that’s why I brought this for you. What about the magazines?”

Kevin worked in an office in mid-Manhattan, and almost daily he saw Hare Krishna devotees chanting on the streets or distributing literature in the subways. He brought me whatever literature they gave him in exchange for his occasional donations of pocket change. Over a few months I had acquired three or four Back to Godhead magazines, which I’d flipped through and tucked under the stereo.

“Mostly looked at the pictures,” I said. “Some really beautiful art. You know, I thought Hare Krishna were just die-hard hippies, trying to be Siddhartha or something, but I’m really beginning to respect them.”

Kevin was noncommittal. “They seem sincere,” he said, “but that’s not my scene.”

Kevin had an innate aversion for spiritual life. He wasn’t an out-and-out hedonist, mind you; he believed in the golden rule. He reckoned his observance of it took care of his end of life’s bargain. He had no objection to my interest in spiritual life, however, and in his own quiet way he encouraged me by bringing me the booklet and the magazines.

While Kevin fixed dinner, I started on the Reservoir of Pleasure. I had enjoyed the other Hare Krishna books, and I was eager to see what a booklet with such a promising title would yield. My eagerness paid off right in the first paragraph:

Each of us, every living being, seeks pleasure. But we do not know how to seek pleasure perfectly. With a materialistic concept of life, we are frustrated and every

step in satisfying our pleasure because we have no information regarding the real level on which to have real pleasure.

Not very earthshaking statements at first glance. In most instances I would have just kept on reading, the way Archimedes might have blithely taken his bath with no further thought about the overflowing water. But he didn’t, because all at once the significance of the overflowing water overwhelmed him. Similarly, I was overwhelmed by the passage; it struck me like a blow between the eyes.

The more I thought about the import of those few sentences, the more they made sense and the more the truth of them became etched into my mind. I felt myself enter an altered state of consciousness wherein I perceived with profound clarity that these statements weren’t merely true, the were absolutely true.

My thoughts gathered momentum. The experience was like a voice speaking to me from within. “This is the challenge of life,” it said. “You have to search out perfect happiness. If you don’t, your life will be worthless. After tonight, unless you do everything in your power to find perfect happiness, you will never be satisfied.”

“That’s it,” I thought. “That’s the whole problem of life summed up right there. Without consciously and deliberately seeking a solution to this problem, what is the value of any other endeavor? Now I understand what Socrates meant when he said, ‘The unexamined life is not worth living.’ “

I went into my bedroom and closed the door. I didn’t want to risk Kevin’s diverting my thoughts before I had fully digested them.

My eureka experience actually had it’s roots in an episode that had occurred about a month earlier. I hadn’t seen my parents since the previous fall, so one balmy Saturday morning I went by bus to New Jersey to spend the day with them. That evening, just before my return journey, Irwin, my stepfather, said, “Conrad, I have a little gift for you,” and popped three books into my hand. They were a trilogy entitled Krishna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

“Hare Krishna books,” Irwin said with a huge grin. He was enjoying himself, getting a kick out of giving me some books by the weird Hare Krishna. “You like books on mysticism and that kind a thing, right?”

“Yeah, I even have a few Hare Krishna magazines,” I replied, feigning interest in Krishna literature to appear appreciative of his gift.

Irwin was the personnel director at Saint Barnabas Hospital for Chronic Diseases, in the Bronx. He had gotten the books from his assistant, who had gotten them from a devotee in the New York Port Authority terminal. His assistant didn’t want the books, so Irwin, thinking I’d be interested in reading up on Hare Krishna philosophy, had offered to take them.

Irwin opened one of the books. “Look at that,” he said. “George Harrison wrote the foreword. You like him, right?”

“O, yes, he’s one of my favorites. I don’t know about the Hare Krishna, though. I always avoid them down where I work. I see them chanting in Central Park on the weekends; they’re a little too flamboyant for me “

“You can say that again,” Mom said. “I think they’re all a little weird myself. Anyway, at least reading one of their books is better than being seen with them in public.”

Walking to the bus stand, I had no intention of reading the books. Although I considered myself a broad-minded spiritual eclectic I would read any book, tract, or magazine by anyone claiming to be a spiritual luminary my eclecticism did not extend to the Hare Krishna. Early on I had ruled them out from serious consideration. Too fanatic, I thought. Too public. Too loud about their spirituality. In my view, being spiritual was fine, but proselytizing on street corners was not. Although a part of me admired the devotees for their courage of conviction, that wasn’t enough to make me want to read their books.

But a bus ride from Teaneck to New York in the late evening is boring, and I’m the type of person for whom any printed matter is grist for my reading mill. Besides, I did want to know what George Harrison had to say about the enigmatic Hare Krishna. So, despite my reluctance, I opened Volume One and started reading his “Words From Apple.”

I read all the way home and on, until two the next morning. I found everything about the book fascinating: the cover, the foreword, the preface, the introduction, the illustrations, and the stories themselves. They were a summary translation from Sanskrit of Krishna’s pastimes in India five thousand years ago. Srila Prabhupada’s lucid commentary ran throughout the narrative. I was amazed to learn of the deep philosophy and tradition behind the people I’d seen chanting in the streets.

Reading at every spare moment, day and night, I finished all three volumes in a few days. One thing I readily appreciated was the historical account of Krishna’s life. I had read Bhagavad-gita and numerous books citing the Gita, but it had never occurred to me to think of the speaker of the Gita, Krishna, as an actual historical person. He was usually portrayed as a mythical person, one whose existence was incidental, not instrumental, to the ideas in the Bhagavad-gita. It was enlightening to learn about His life, both before and after He spoke the Gita.

At the same time I made a grievous mistake. I took particular relish in identifying myself with Krishna, the way a person might vicariously enjoy the role of the hero in a story. I imagined that the descriptions of Krishna’s pastimes were a sample of the kind of pastimes I would enjoy when I became enlightened and realized that I too was God.

In those days I was an impersonalist. I believed that I was God, somehow temporarily fallen into illusion and therefore forgetful of my true identity. I thought the aim of spiritual life was to realize my “godself” and merge back into the Universal Oversoul. This, I thought, was the heart of India’s Vedantic philosophy, for that was the slant of virtually every book on the subject that I’d read prior to Srila Prabhupada’s.

Never having encountered personalism (the doctrine that the individual souls are eternal persons and loving servants of the Supreme Eternal Person), I had wrongly assumed Srila Prabhupada to be of the same impersonal persuasion as myself. I therefore interpreted all I read in his books in impersonalistic terms.

Reading the same books now, I see clearly that the impersonal conception is a prime target of Prabhupada’s strong personalistic commentary. I wonder at how I was so foolish as to twist his words to suit my preconceived notions of spirituality. I’m embarrassed to admit that despite my fascination with the pastimes, I had no solid understanding of Krishna consciousness after reading the Krishna trilogy.

What I did gain, however, which helped prepare me for my eureka experience, was a willingness to read more books by Srila Prabhupada. Though I hadn’t properly understood the trilogy, I was convinced that Prabhupada was a genuine self-realized spiritual authority, that he wasn’t just conjecturing about transcendence.

My conviction about Prabhupada’s spiritual authority came in handy when I read the Reservoir of Pleasure. Because I had enjoyed the trilogy, I was more receptive but not uncritically so to what Prabhupada had to say.

In one sense, my realization that night was not unique. Many others have come to similar conclusions about life. That wasn’t even the first time I had had thoughts about the frustration of my desires for pleasure. What made it unique were the clarity with which I saw the truth of Prabhupada’s words, and the conviction that perception brought me. It galvanized me with resolve to make the search for perfect pleasure my priority. I knew I would never be able to ignore this experience and simply meander through life.

As I read on, I was that Srila Prabhupada proposed Krishna consciousness as the process for realizing perfect pleasure. All his arguments made sense to me, but I wasn’t convinced yet; I wanted to study his teachings more carefully. At the same time, I decided that if accepting the path to perfect pleasure meant shaving my head, wearing robes, and singing and dancing in the street, I would do those things. They seemed a small price to pay for the thing I wanted more than anything else in the world.

I was cautious, though. I went to the Krishna temple in Brooklyn to see if devotees practiced what Prabhupada preached. I was pleased to see that they did. I read more of his books Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Teachings of Lord Caitanya, The Nectar of Devotion, and Sri Isopanisad and found no inconsistency in the philosophy. I started visiting the temple twice daily, attending morning and evening classes, and chanting with the devotee in Times Square.

By the end of July, I could no longer bear living a dual life, so I tendered my resignation at White, Weld and Co. In giving my reasons for quitting, I quoted the lyrics from a song by Cat Stevens that had been coursing through my mind for several months:

I don’t want to work away

doing just what they all say

word had boy and you’ll find

one day you’ll have a job like mine,

job like mine, a job like mine.

Be wise, look ahead, use your eyes,

they said. Be straight. Think right.

But I might die tonight.

doing just what they all say

word had boy and you’ll find

one day you’ll have a job like mine,

job like mine, a job like mine.

Be wise, look ahead, use your eyes,

they said. Be straight. Think right.

But I might die tonight.

And I gave my closing comment: “There must be more to life than a promising future in a lucrative dog-eat-dog career on Wall Street, and I’m determined to find it.” Two weeks later I moved into the temple.

That fall my eureka experience bore its first fruit. My conclusion about Srila Prabhupada being a genuine self-realized soul was confirmed in a most wonderful way, leaving me no room for doubt. He came to New York, and the devotees went en masse to greet him at the airport.

He carried himself with a childlike innocence I had never seen before; he seemed to be the humblest person I’d ever seen. Yet he was regal in his bearing aloof, but not at all haughty. His countenance was sublime.

Right away I knew I was in the presence of a saint. I was stunned. In my thinking, saints were beings so rare as to be mythical, like unicorns. I had relegated saints to religious storybooks. I had never dreamed I would meet a real one face to face.

Along with the devotees present, I bowed to him, my head touching the floor as I recited in Sanskrit two prayers I’d learned at the temple:

I offer my respectful obeisances unto His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who is very dear to Lord Krishna, having taken shelter at His lotus feet.

Our respectful obeisances are unto you, O spiritual master, servant of Sarasvati Gosvami. You are kindly preaching the message of Lord Caitanyadeva and delivering the Western countries, which are filled with impersonalism and voidism.

Before rising, I vowed to follow Srila Prabhupada for as long as I lived. Immediately my whole being felt light, as if a great burden had been lifted off me. I felt happiness beyond anything I’d ever felt. It was an incomparably ecstatic, rapturous feeling.

To this day I have no idea why the opening passage of the Reservoir of Pleasure had such an overpowering effect on me. I have thought about it over the years, and I can think of no explanation, except a simple admission that it was Krishna’s mercy.