An Intellect Discovers Its Perfection

The profound philosophy and devotional nectar of the Vedic scriptures whets a brilliant student’s appetite.

I was born with a congenital heart deformity that doctors said would probably not allow me to see my fifth birthday. When I was around one, learning to walk in our middle class house, I suddenly collapsed on the ground, never to walk naturally again. My parents, Ramachandra Pujari and Sunanda Pujari, had me vaccinated against the dreaded polio infection rampant in India in the 1970s, but the doctor had accidentally given a defective vaccine. With my left leg diseased, I had to walk either with a limp or with a brace. When I was around two, enjoying the spectacle of the popular Dipavali firecrackers with the neighborhood children, suddenly a rocket firecracker intended to fly high into the sky got misdirected to me. All the other children ran away, but, due to my lame leg, I couldn’t. The rocket hit my right arm, fusing my shirt with my skin, and raced upward, burning my face, missing my right eye by millimeters. It then fell to the ground, leaving lifelong scars on my right arm and the right side of my face. When I was three, I fell from a wall near my house, cracking my skull. An astrologer told my despairing parents that I was plagued by Saturn, who would cause repeated trouble for the first seven and a half years of my life.

SHELTER IN THE INTELLECT

My parents did everything in their power to help me have a normal childhood. They decided not to have another child for a decade so that they could give their full attention to caring for me. They admitted me into an expensive Christian convent school so that I could have the best education. Their sorrows were somewhat mitigated when they found me getting good grades. My parents would tell visiting relatives that God had compensated for my physical inabilities by bestowing intellectual abilities upon me. I would wonder about this mysterious being, God, who had the enormous power over my life to decide what to give and what to take. For my parents, who were brahmanas by caste, religious rituals were an important part of the family culture. My father told me the significance of our surname Pujari, which meant a priest who worships the Deity by offering püja. About a century ago, his grandfather, while bathing in a river one early morning in our native village, had found a five headed Hanuman deity floating, which he had subsequently installed and served as püjari.

My daily life with its pursuit of academic excellence had little in common with my religious ancestry. At school, as my grades kept getting better, it seemed Saturn had left me. In my tenth standard matriculation exam, I was among the state toppers. The district collector (the top government officer of the district) visited our house to congratulate my parents and the local newspaper carried an article and a photo of the visit. For my parents, life seemed to have turned a full circle. In the past, they had shed so many sad tears over their son. Now at last they had occasion to shed tears of pride and joy.

Unfortunately, the joy was short lived; the merry go round of life suddenly took a nasty nosedive. The very day our family photo came in the newspaper, my mother, while doing a medical checkup, was diagnosed with advanced leukemia. She fought gallantly against the cancer with chemotherapy, but within one painfully long month, it was all over.

As the world around me collapsed, I sought shelter in my studies and my academic performance.

FROM SUMMIT INTO QUICKSAND AND OUT

While studying for an engineering degree at a leading college in Pune in 1996, I gave the GRE exam for pursuing post graduate studies in the USA. I came first in the entire state, securing the highest score in the history of my college. As I exulted in my greatest achievement, I experienced something perturbing. Until then, society had led me to believe that for a student academic accomplishment was the ultimate standard of success and happiness. I had feverishly sought that standard and had finally achieved it. Yet as I stood on the summit of success with the trophy score sheet in my hands, I found that the grades themselves brought no joy. It was only when others congratulated me that I felt satisfaction. My happiness depended on others’ appreciation more dependent than ever before. As I pondered on this disturbing experience, it struck me that I had been chasing a mirage: academic achievement, or any other achievement for that matter, would never satisfy me, but would only increase my hunger for appreciation and thus perpetuate my dissatisfaction. The summit had turned into a quicksand.

A friend extended a helping hand to rescue me from the quicksand by giving me Srila Prabhupada’s Bhagavad gita As It Is. The Gita answered many of my questions about life and its purpose, which had been left unanswered by the numerous books spiritual and secular that I had read till then. Whatever questions remained were expertly answered by RadheSyama Prabhu, the temple president of ISKCON Pune and Gaurasundara Prabhu, a dynamic youth mentor at ISKCON Pune. Understanding the profound philosophy of Krishna consciousness illuminated my life’s journey with hope and joy. I understood that my lame leg, which had always interfered with my playing cricket, was a result of my own past bad karma. But it couldn’t interfere with my spiritual life, because, after all, neither was I my body, nor was my spiritual advancement dependent on my body.

The Hare Krishna maha mantra was my next discovery. Since my teens, I had been fighting a losing battle against the passions of youth, which would often sabotage my intellectual pursuits. In the chanting of the holy names, I discovered the technology to sabotage those passions.

THE HIGHEST EDUCATION

But the best was yet to come. As I studied the books of Srila Prabhupada and his followers, especially their writings based on the Bhagavad gita, I found myself relishing the study itself. This was in marked contrast to my earlier academic studies, where the joy was primarily in the grades got from the study. Then I read in the Srimad Bhagavatam about the super intellectual sage Vyasadeva. His phenomenal literary achievements in writing scores of Vedic literatures failed to satisfy him, but exclusive glorification of the Lord fully satisfied him. As I read the story, I felt as if my life story was being replayed in front of me but with the future included. I recognized the principle that intelligence could bring real happiness and do real good to oneself and others only when used to glorify Krishna and that principle showed me my future.

I started using my intelligence to share the philosophy and practices of Krishna consciousness with my college friends. To my amazement, I found several of them becoming remarkably transformed, shedding their bad habits and leading balanced, healthy, happy lives. After my graduation in 1998, I found myself at crossroads that I had already crossed internally. Though I had both a lucrative job as a software engineer in a multinational company and an opportunity for education in a prestigious American university, an overpowering inner conviction told me that I could serve society best by sharing the spiritual wisdom that had enriched my life. There was no shortage of software engineers in India or of Indian students in America, but there was an acute shortage of educated spiritualists everywhere.

But another crossroad still remained. Far more difficult than sacrificing a promising career was enduring the disappointment in the eyes of my father. In traditional Indian culture, aging parents are often taken care of by their grown up children, but I knew that the loss of such care was not my father’s concern. By his expertise at managing his finances, he had attained reasonable financial security, and he also had my brilliant eleven year old younger brother, Harshal, to count on. His heartbreak was to see his older son, for whose materially illustrious future he had dreamt and toiled, become the antithesis of his dreams: a shaven headed, bank account less, robe wearing monk. His distress agonized me, but my heart’s calling left me with no alternative. I prayed fervently to Krishna to heal my father’s heart and to somehow, sometime help him understand my decision.

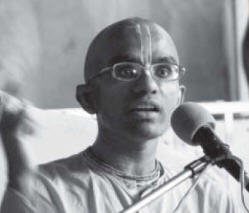

So in 1999, I decided to make sharing the wisdom of the Gita my fulltime engagement by joining ISKCON Pune as a brahmacari (celibate teacher). In 2000, I received initiation from my spiritual master, His Holiness Radhanatha Maharaja, who told me that because I had given up the chance for higher education in the USA for Krishna’s sake, Krishna was giving me the chance to receive and share the highest education: education in Krishna consciousness, which is celebrated in the Bhagavad gita as raja vidya, the king of all

education. In accordance with his instruction, I started giving talks to youths first in Pune and then all over India. By Krishna’s mercy, my lame leg has not been a hindrance even up to this day.

education. In accordance with his instruction, I started giving talks to youths first in Pune and then all over India. By Krishna’s mercy, my lame leg has not been a hindrance even up to this day.

INTELLECTUAL SAMADHI

In 2002, I discovered writing. Since childhood, I had wanted to write, but had not been able to: I was never short of words (my favorite hobby was memorizing words from dictionaries), but I always seemed short of ideas. The rich philosophy of Krishna consciousness more than made up for that shortage. Over the last seven years, some 150 articles and 6 books have emerged from my computer keyboard. Many of these articles have appeared in leading Indian newspapers and some in Back to Godhead. When my first article appeared in the reputed Times of India newspaper, my overjoyed father sent a hundred photocopies of that article to his relatives, colleagues and acquaintances. When I see the joy in my father’s eyes on seeing every new book that I write, I thank Krishna for answering my prayers.

By the end of 2009, I was invited by the BTG editor Nagaraja Prabhu to serve as one of the associate editors for the magazine. The service of reviewing articles with the other editors, who are all learned and seasoned devotee scholars, broadened the horizons of my spiritual understanding more than anything else I had done before this.

For me personally, writing itself not so much its fruit has brought meaning, purpose, passion and fulfillment. Although I am still a neophyte in my spiritual life, struggling against selfish desires, writing does give me glimpses of samadhi, blissful absorption in thoughts of Krishna and His message.

Having experienced both the emptiness of material intellectual pursuits and the richness of spiritual intellectual engagements, I feel saddened that most modern intellectuals are deprived of this supreme fruit of their intellects. Many Indian intellectuals, despite earning material laurels at a global level, are still missing the intellectual feast that their scripturally learned ancestors relished for millennia. My writings are humble attempts to help them rediscover their lost legacy. I look forward to utilizing the remainder of my life, relishing and sharing the intellectual devotional nectar I have been blessed with.

Caitanya Carana Dasa has a degree in E&TC engineering and serves full time at ISKCON Pune. To read his other articles visit thespiritualscientist.com