Memories and Reflections on The Power Of The Holy Name

Though seemingly chance encounters, the holy name of the Lord gradually brings light to a struggling soul.

CAMBRIDGE MASSACHUSSETTS, USA. December 1970.

Walking along a commercial street in a blizzard, we spot a group of orange-clad people singing across the street.

“Maybe some Buddhists protesting against the Vietnam war,” I tell Marc, my husband. Blowing cigarette smoke I walk on, and so does Marc.

“By sound vibration one becomes liberated,” says the Vedanta-sutra.

Unknown to me, my spiritual life had begun. The people on the Cambridge sidewalk were not Buddhists but representatives of Lord Caitanya, performing harinama-sankirtana, the congregational chanting of God’s holy names.

Lord Caitanya, who is nondifferent from Lord Krishna, started the sankirtana movement five hundred years ago to uplift the degraded human beings of this age. I was eligible. Born and bred in France, I embodied the mood of a generation led by Sartre and Camus proud, confused, and miserable.

Marc, however, believed in God and the so-called good things in life. Our odd combination lasted less than five years. By the time it ended we had settled in South Africa and I was teaching French at the Alliance Francaise in Johannesburg. A man of Indian descent attended my classes. Everybody called him Krishna, and so did I.

“Living beings who are entangled in the complicated meshes of birth and death can be freed immediately by even unconsciously chanting the holy name of Krishna, which is feared by fear personified,” says the Srimad-Bhagavatam.

By putting that man into my classroom, the merciful Lord had tricked me into chanting His holy name.

A year later I met a girl who said that God was a blue boy who played the flute. Her statement made no difference to me. But as fate would have it, the girl, Denise, entered my circle of friends, along with a tape recorder that played the same song over and over again: “Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.” The rhythm was lively, with shell horns blowing in the background. And the sound was nice, except that I had to hear the same thing over and over again every day. Strangely enough, that didn’t bother me as much as I thought it would. But when another girl my best friend became a vegetarian and started singing the song as a daily meditation, I decided to move on.

“The treasure of love of God has descended from the spiritual world of Goloka Vrindavan, appearing in this world as the sankirtana movement of the chanting of the names of Lord Hari, Krishna. Why am I not attracted to it? Day and night I burn from the poison of material existence, but still I refuse to take the antidote.”

This song by Narottama Dasa Thakura, a sixteenth-century saint of the tradition of Gaudiya Vaisnavas (followers of Lord Caitanya), pretty well summed up my situation.

I roamed around for a year or so before again settling down to a “permanent” job and residence in Johannesburg. Ten months later I gave them up and moved to the countryside to write, sing, play the guitar, and forget about the world. To be more in harmony with nature, I became a vegetarian.

One day I ran into Denise in downtown Johannesburg. She was carrying a copy of Bhagavad-gita As It Is, which she tried to sell me. I was dead set against reading anything religious, but it looked like the best book I’d seen since a bilingual edition of The Divine Comedy I’d picked up in Paris years before. I couldn’t resist buying the Gita.

Back in my cabin I looked at the Sanskrit text with pleasure. But the English translation didn’t make sense to me. What did “spirit soul” and “modes of material nature” mean?

A passage I read at random collided with my atheistic bend: “Men who are ignorant cannot appreciate activities in Krishna consciousness, and therefore Lord Krishna advises us not to disturb them and simply waste valuable time. But the devotees of the Lord are more kind than the Lord because they understand the purpose of the Lord. Consequently they undertake all kinds of risks, even to the point of approaching ignorant men to try to engage them in the acts of Krishna consciousness, which are absolutely necessary for the human being.”

“Just see,” I thought, “these people can’t even stick to their Lord’s command. He is telling them to do one thing, but they think they know better. This book is useless.”

“These books I have recorded and chanted, and they are transcribed,” Srila Prabhupada said. “It is spoken kirtanas. … Anyone who reads, he is hearing.”

On June 17, 1978, Denise brought me a birthday present a strand of 108 round wooden beads in a white cloth bag and told me how to use it. I had no intention of using the beads. But then, just a few days later, I picked up the bag on my way out for a walk. Fingering the beads I recited timidly: Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. After a minute or two I gave up.

“Simply by chanting the holy name of Hari, a sinful person can counteract the reactions of more sins than he is able to commit,” says the Brhad Visnu Purana.

Over the past few months I had been thinking a lot about “entering eternity.” Although I had no idea how to do it, I had concluded that I would have to renounce everything, including my beloved typewriter. One night, just a week after my birthday, two drunken farmers paid me a visit, and their behavior led me to flee the place in disgust. Somehow, the typewriter and guitar went off with me, but everything else stayed behind for the neighbors to enjoy.

“When I feel especially mercifully disposed towards someone, I gradually take away all his material possessions. His friends and relatives then reject this poverty-stricken and most wretched fellow,” Lord Krishna tells King Yudhisthira.

I didn’t realize I was the recipient of the Lord’s mercy, yet the feeling that I had been taught a lesson lingered in my consciousness.

Drifting from one friend’s place to another’s, I again met Denise. She said she wanted to visit the Hare Krishna devotees on their new farm in the hills of Natal, six hundred kilometers east of Johannesburg. She had money but no transport, I had a car but no money, so we drove off together.

I agreed to hold off on smoking and scrupulously followed the regulations during our ten-day visit. On the way back to Johannesburg I was happy with the experience but never thought of even trying any of the spiritual practices I’d learned.

I got a room in a rundown area of town and sat there for the next six weeks, surviving on oranges and sunflower seeds. My mind was made up: I was through with jobs, love, friendship, society, and philosophical research. I gave my car to a friend and resolutely waited for something to happen.

One day while bathing, a thought struck me: “What is the significance of this body?”

The Bhagavad-gita As It Is lay on the table, impenetrable. The round wooden beads hung on the wall in their white cotton bag. I picked them up. “Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare.”

“I want to do the right thing,” I thought, ” whatever it is.”

A week later Denise got hold of me.

“Hey,” she said. “There’s a car going to Durban tomorrow. Why don’t you catch a ride to the farm and spend a couple of weeks there?”

I packed the few clothes I’d received from well-wishers, stored the guitar and typewriter, and caught the ride.

From the highway I walked a few kilometers down the footpath and found the Hare Krishna farm I’d visited less than three months before. The place was bustling. Standing by the kitchen, I heard pots clanging and saw devotees with utensils in their hands rushing around.

Ranajit Dasa spotted me.

“Hare Krishna,” he said. “You’ve come on a very auspicious day. Today is our spiritual master’s disappearance day.”

I didn’t understand what that meant, nor did I really care to know. Some Indian girls took me to the women’s asrama and wrapped me in a sari.

It is said that the spiritual master is especially merciful on the anniversaries of his appearance (birth) and disappearance (passing). His Divine Grace Srila Prabhupada surely bestowed special mercy upon me on the first anniversary of his disappearance. How else could I have stayed in the association of devotees until now?

Today, rereading the Bhagavad-gita purport that upset me so much eighteen years ago, I wonder at Srila Prabhupada’s boundless compassion. Had Srila Prabhupada followed Lord Krishna’s recommendation and stayed in Vrindavan to relish his own Krishna consciousness, the transcendental seed of love of God would not have sprouted in the hearts of those great souls who braved the Massachusetts blizzard just to purify the unwilling ears of fools and rascals like me.

“Oh, how glorious are they whose tongues are chanting Your holy name!” says Devahuti to Lord Kapila. “Even if born in the families of dog-eaters, such persons are worshipable. Persons who chant the holy name of Your Lordship must have executed all kinds of austerities and fire sacrifices and achieved all the good manners of the Aryans. To be chanting the holy name of Your Lordship, they must have bathed at holy places of pilgrimage, studied the Vedas, and fulfilled everything required.”

Lord Krishna says, “A self-realized soul sees with equal vision a gentle and learned brahmana, a cow, an elephant, a dog, and a dog-eater.” Srila Prabhupada had such vision. Knowing every living entity to be the eternal servant of Krishna, he didn’t consider whether a person was qualified to hear the holy name or not but gave equal opportunity to everyone. He proved that devotees of the Lord are more kind than the Lord because they understand the purpose of the Lord to take everyone back home, back to Godhead.

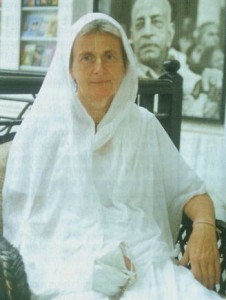

-priya Devi Dasi lives at ISKCON’s Krishna-Balarama Mandir in Vrindavan, India. She works with the Vaisnava Institute of Higher Education (VIHE).